Amid deepening strategic competition between Beijing and Washington, China’s dominance over a number of critical raw material value chains is a clear source of vulnerability. The increasingly pervasive use of economic statecraft and the shift toward a weaponization of economic interdependencies has pushed the issue to the top of the policy agenda in both the United States and Europe. Indeed, critical metals are China’s wildcard. But the increasingly zero-sum competition to secure access to raw materials for the industries of the future risks complicating efforts to ensure that supply chains are both more resilient and sustainable.

China’s Supply Chain Dominance

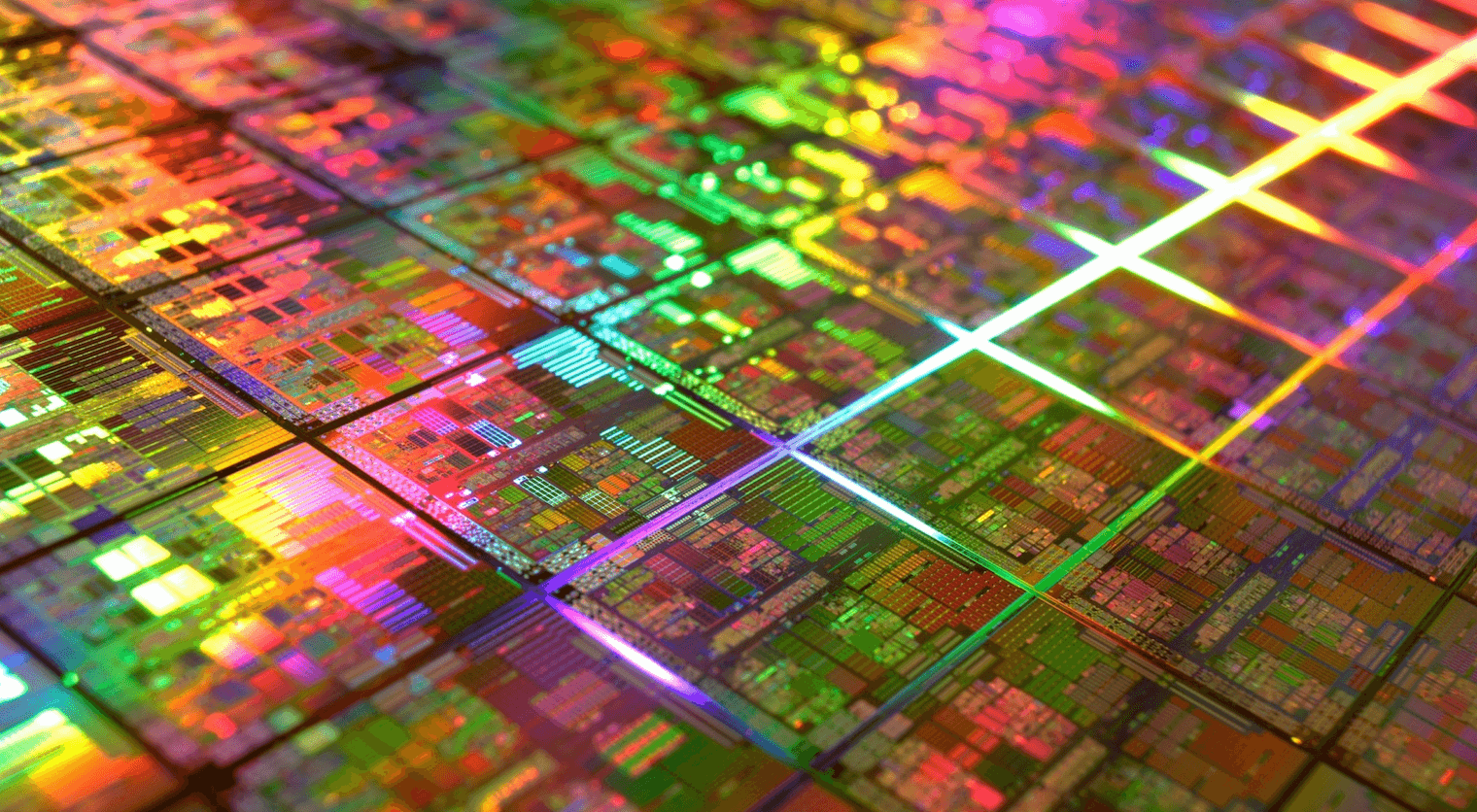

China maintains a clear dominance over supply chains for several raw materials that are essential to a successful transition toward a digital, carbon-neutral future. For some minerals, mines in China supply the bulk of global production. China mines over 60% of the world’s rare earth elements, for instance, which are used in a broad range of critical applications, notably permanent magnets that are essential components in motors for electric vehicles or offshore wind turbines. More broadly, of the 35 minerals that the Unites States Department of the Interior classified as “critical” to its economy and national security in 2018, China is the majority producer of 13, for 7 of which its mines produce more than 70% of global supply. In other cases, for instance lithium, cobalt and nickel, essential components for battery manufacturing, China has moved to secure a central place in mining operations overseas. But more than the extraction of the minerals themselves, China has also established a dominant position in downstream processing. Nearly 90% of rare earth processing is done in China, which then produces 92% of the world’s permanent magnets. China processes 40% of the world’s copper, 35% of nickel, 58% of lithium, 65% of cobalt and 70% of graphite. It then produces over 70% of the world’s cathode and 80% of anode battery cell components, and accounts for over three quarters of the world’s final assembly of Lithium-ion batteries. China’s dominance of the solar photovoltaic value chain is even more pronounced.

Risks of Weaponization and Washington’s Search for Resilience

In the face of China’s dominance across a number of important sectors, the United States, as well as Europe, have found themselves in an uncomfortable position of dependence. For the time being, Beijing’s weaponization of its strategic wildcard, namely by cutting off supplies, remains largely theoretical. China’s de-facto embargo of rare earth exports to Japan in late 2010 has largely set the tone for considering the supply risks, but it remains the only clear example, and one for which Beijing’s the intention is still a matter of debate. In 2019, as the Trump administration ramped up its trade war, Chinese president Xi Jinping made a public visit to a leading rare earth magnet manufacturing plant of JL Mag to demonstrate the potential for China to leverage its dominant position in this strategic sector. But in the end, such levers have remained untouched in the context of US-China competition. Beijing appears fully aware that a weaponization of its supply chain advantages would trigger a broader escalation of tensions that would undermine its own economic interests. China’s priority remains its own economic development, ensuring resource security for its growing domestic needs and bolstering competitiveness in key sectors, such as electric vehicles.

Nevertheless, as tensions with Washington mount, including through efforts to freeze China’s technological development in place, and in the event of a more direct confrontation, for instance over Taiwan, China’s raw material supply chain advantages could eventually be mobilized to serve broader strategic ends.

Meanwhile, responding to China’s asymmetric advantage in critical raw materials is being treated with an increasing sense of urgency in the United States. During the Trump administration, the United States moved quickly into a posture of exploring and developing mineral deposits and building supply chains domestically, in the context of a broader approach of reshoring and national reindustrialization. Starting in 2020, for instance, the Department of Defense began funding the development of rare earth processing facilities in California and Texas, slated to come online by 2025. The Biden administration has redoubled the government’s efforts, making domestic supply chain development for critical minerals a national priority, particularly in light of its efforts to drive the low-carbon energy transition. Indeed, mineral security has been a feature of prominent legislation passed in the last two years, notably the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

Europe Challenged by Zero-Sum Competition

Of these measures, the IRA, passed in July 2022, is proving to be the most problematic for Europe. In addition to tax credits, loan guarantees and direct public spending to bolster domestic production and processing of critical raw materials worth upwards of USD 70 billion, the legislation includes protectionist measures such as revised electric vehicle tax credits, requiring that battery materials be sourced domestically. An exception has been provided for partners with which the US has a free trade agreement, but no such pact exists with the EU. This has strained Trans-Atlantic cooperation at a moment when the bloc is redoubling efforts to bolster its own mineral supply chain resilience in the face of challenges from both China and Russia, for instance through the Critical Raw Materials Act adopted in March 2023. Critical mineral markets are already under strain from rapidly increasing demand and severe environmental challenges that will come with a dramatic ramping up of mine production. Strategic rivalry, trade protectionism and zero-sum competition will only create needlessly wasteful duplication and complicate efforts to ensure that supply chains will not only be more resilient, but more sustainable.