The multifaceted competition between China and the United States is not restricted to our planet: it has also extended to the realm of space. An essential component for any great power, space programs allow states to acquire prestige linked to technological know-how and scientific excellence, to benefit from the economic and social development enabled by civil applications, and to strengthen national defense through military applications. In its quest for power, China sees space as a sector in which it must play catch-up, while the United States is keen to maintain its advantage. Meanwhile Russia, the world’s first space power, now finds itself watching from the sidelines. It is firmly on Beijing’s side, but it appears to be a secondary actor. The Russian space industry is in a state of decay, exacerbated by the war in Ukraine.

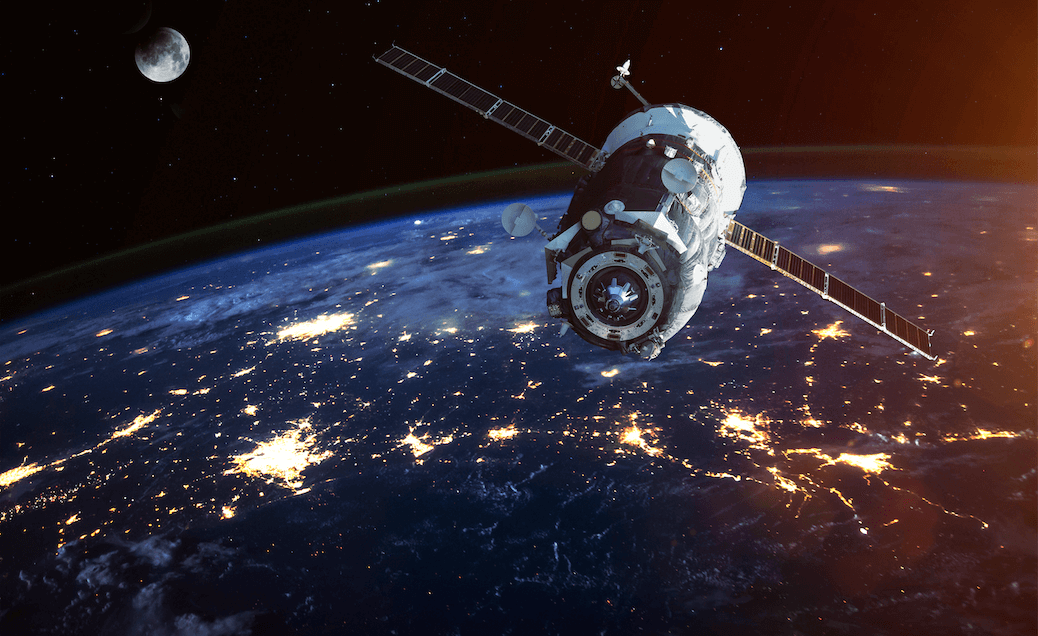

Sino-American competition in the space domain is all-encompassing, but three areas in particular appear to be especially important: the race to the Moon, space stations in low Earth orbit, and satellite internet constellations.

The Race to the Moon

In the 1960s, the race to the Moon pitted the Americans against the Soviets. Today, the United States and China are the two key rivals in this race. They have each announced relatively similar ambitions and timelines. Both countries aim to build a permanent and inhabited base on the surface of the Moon in order to exploit its resources and subsequently establish a spaceport for Mars.

These two competing programs present themselves as international. The United States’ lunar program, Artemis, is open to cooperation via the eponymous accords, signed by twenty-three states, including several EU member states: France, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, and Romania. Its competitor, the International Lunar Research Station, is a joint program between China and Russia. Although it is open to the rest of the world, there are currently no other known partners. However, Russia’s present situation threatens to undermine the viability of the project. Moscow’s isolation on the international stage could deter potential partners, while its financial and technological vulnerability as a result of the sanctions it has faced could hinder its capacity to honor its commitments. Beijing, nevertheless, believes that it will be able to meet its objectives, with or without Russia.

The race has only just begun, but for now the Americans have a certain advantage owing to their experience and their technological edge, thanks in particular to the Space Launch System, the most powerful rocket currently available, which was developed by NASA and successfully tested in November 2022. In China, the Long March 9, which will be used for the lunar program, is not expected to be ready until 2030 at the earliest. The United States also benefits from a wide network of international partners providing technical and political support.

Space Stations

Closer to home, in the low Earth orbit domain, China has emerged as a leading scientific actor with its Tiangong 3 space station, whose assembly was completed in autumn 2022. Beijing thus now has a permanently inhabited space laboratory. Tiangong 3 is about a quarter of the size of the International Space Station (ISS)—around 100 metric tons, compared to 420—but it could become the only laboratory in low Earth orbit, given the uncertain future of the ISS, which could be deorbited or entrusted to the private sector in the years to come. The prospect of a future Chinese monopoly must be relativized since, for the Americans, the objective is circumlunar orbit.

Low Earth Orbit Satellite Internet Constellations

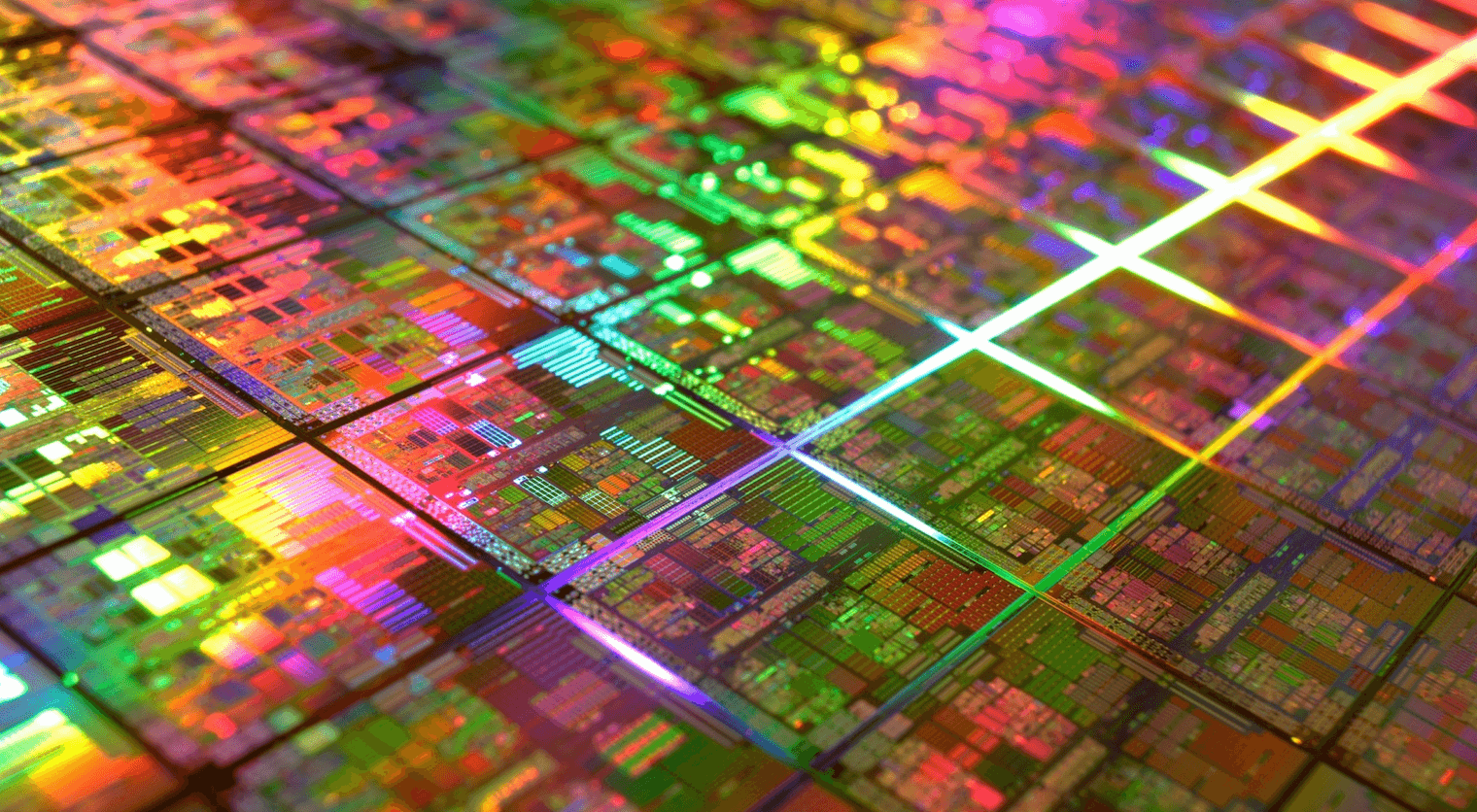

Among the numerous space applications that we use on Earth, low Earth orbit (LEO) satellite internet constellations hold a great deal of promise, not only in the civil and military domains, but also in the commercial domain. The Americans have a significant lead in the commercial space sector thanks to Elon Musk’s Starlink constellation, which currently consists of around four thousand operational satellites in orbit. Starlink has also proven itself in a theater of conflict by providing the Ukrainians with a resilient telecommunications system.

China, meanwhile, is lagging behind somewhat, but it is building up its industry in order to position itself on this market and eventually compete with Starlink. In May 2021, the Chinese government created the state-owned enterprise China SatNet with the mission of developing and operating the future constellation Guowang. China has obtained authorization from the International Telecommunication Union for the launch of 12,992 satellites, nearly 1,000 more than Starlink. It could launch its first satellites between 2023 and 2025, but the Chinese authorities remain tight-lipped about their timeline and their ambitions.

Europe in the Space Competition

Europe remains an important space actor on the international stage, but it faces major challenges: limited resources, fierce competition, uncertain ambitions, and the growing geopolitical polarization between China and the United States. In this context of polarization, Europe, which has traditionally been open to cooperation with all actors in the space sector, must review its partnerships. This is already the case for Russia, and there are now serious questions surrounding China as well. The United States is becoming Europe’s favored partner, although the unilateralist approach to space governance promoted by Washington contradicts the multilateral model defended in Europe.

To maintain its position as a space power, but also its influence and its ability to promote its own vision of space governance, Europe must maintain and strengthen its autonomy in access to space, surveillance and tracking capabilities, Earth observation, and space-based telecommunications.