Global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2022 have been rising again, with prevailing policies putting the world on track for a 2.5° C rise in global temperature by the end of the century. Climate change is increasingly framed as a matter of technological and industrial competition between China and the United States of America (USA), rather than cooperation for the public good, and marked by rising North-South tensions. China is the world’s largest emitter (nearly 31% of GHG emissions in 2021) and the second-largest national one after the US in terms of cumulative CO2 emissions, being responsible for 60% of the increase in global CO2 emissions between 2010-2019. Over the period 1990-2020, US GHG emissions were reduced by 7.3%, and the country accounted for 13.5% of global emissions in 2021. By contrast, the EU achieved a GHG emissions reduction of 33% over the same period and accounted for about 7.5% of global GHG emissions in 2021.

Views and interests among these players do not converge. The US wants to decarbonize to lead the technological race started by China with its Made in China 2025 plan, and to de-couple from Chinese manufacturing of clean technologies. The EU has been trying to accelerate its energy transition and achieved more than the two others in terms of decarbonization, yet just lately prioritizing issues of industrial policy and competitiveness. However, the case for action on climate change and environmental protection has never been stronger: China and the US are involved in global discussions. They achieved progress in the past, and their efforts should be reinforced.

Fundamentally Different Approaches to Climate Change Action

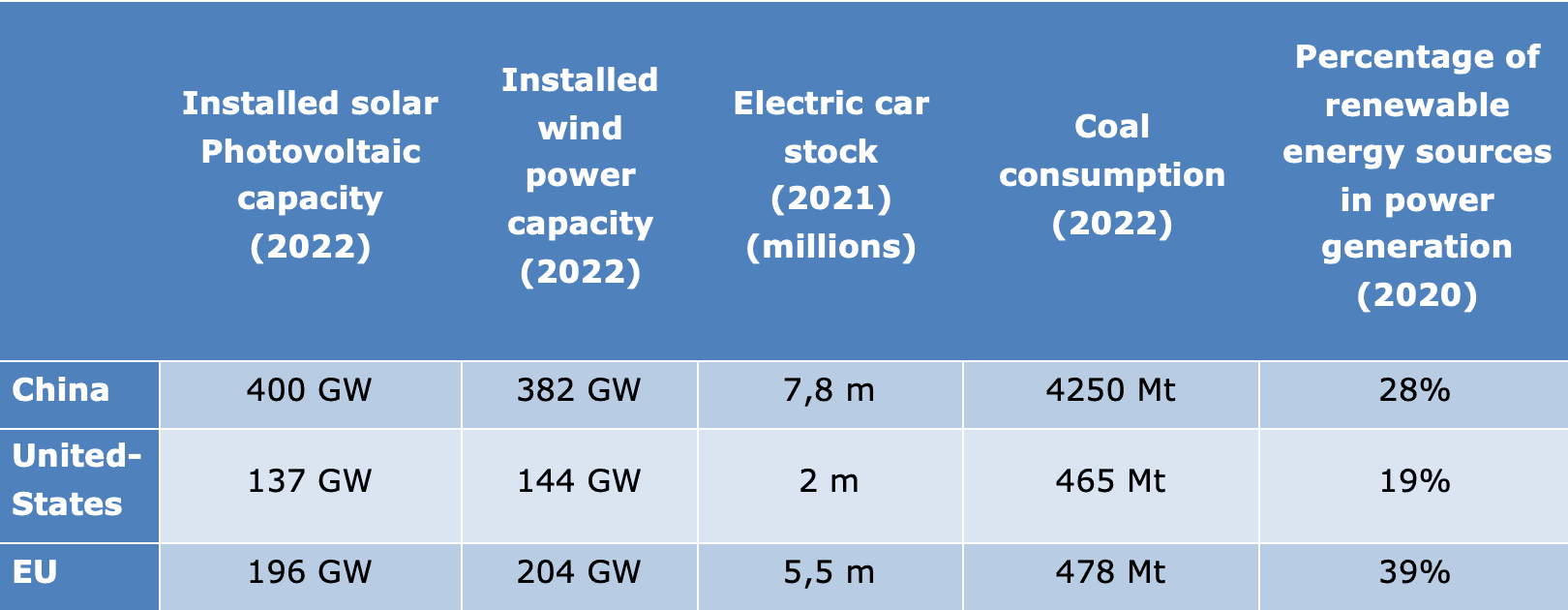

On climate, China has been shying away from committing to ambitious targets (its “1+N” policy aims at peaking emissions before 2030 and becoming carbon neutral by 2060, but without any specific commitments after 2030). Strengthening energy security and ensuring social stability takes priority over rapid decarbonization (in 2020, China had around 250GW of coal fired capacity under development). At the same time, China has been massively subsidizing and deploying domestic low-carbon technologies, making the global energy transformation largely dependent on these. The world, and namely the US and the EU, are waking up to a reality where China has the first mover advantage on the super large scale “green” industrial policy.

On its side, the US experiences ebbs and flows in climate ambition depending on internal politics (i.e., not ratifying the Kyoto Protocol, “in and out” commitment to the Paris Agreement, not ratifying the Convention on Biological Diversity). At the same time, there is a bipartisan determination to stay ahead of the technological race (ex. Chips Act, Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Inflation Reduction Act - IRA) and keep a competitive edge against China, committing huge tax credits to incentivize investment to this end, some trade barriers and restrictive export control policies.

The EU has adopted a largely normative approach to climate change mitigation through a steady regulation of CO2 emissions (namely through direct CO2 pricing), mandating energy efficiency and renewable energy deployment obligations. Its commitment to climate action has been going in crescendo thanks to the European Green Deal, the European Climate Law, the Fit for 55 package and further strengthened during the energy crisis entailed by the war in Ukraine (RePowerEU). Toward China, the EU is developing a “de-risking” approach, more in phase with its specificities compared to US’ de-coupling approach.

As things stand currently, outright exemptions from EU’s recently agreed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) can hardly be justified for both US and China. China has made significant steps domestically by putting in place an emissions trading scheme (ETS - limited to the power sector, with a soft take off), a plan to improve the energy and resource efficiency in industries, certain standards for CO2 emissions in buildings and targets for non-fossil fuel electricity generation, EVs and H2 mobility. Nevertheless, the world remains unclear about the concrete decarbonization trajectory in China. The same uncertainty looms over the US pathway. Despite a target of 50-52% of emissions reduction by 2030 and of 100% carbon pollution-free electricity by 2035, policies in place mainly consist of incentives for domestic production and consumption, leaving direct CO2 pricing still out of sight, and emission decline rates way insufficient for a 1,5° C trajectory.

The US’ IRA, the EU’s reaction to it and China’s decision to ban the export of several core solar panel technologies abroad (replicating US’ move on semiconductors) have confined climate action to matters of industrial policy and green protectionism. This excessive focus on industrial policies will be harmful for finding international solutions to fundamental issues like establishing a global CO2 pricing system, regulatory standards for decarbonization of industries, optimizing energy and resource use, etc.

EU: Instilling a Sense of Public Good in Climate Action

EU must have a clear narrative recognizing that it is the only large emitter with effective results and a holistic framework to tackle climate change. While continuing to display a more assertive attitude (e.g., Regulation on Foreign Subsidies, etc.), a critical dialogue should be developed with China on issues such as enhancing transparency and accountability standards to guarantee a level playing field, adopting standards for reducing energy consumption in the digital sector, moving to sustainable aviation fuels, fighting imported deforestation and methane emissions. The EU should also gear its Global Gateway funding toward partnerships with key actors in raw materials and clean energy production, push forward with the implementation of Just Transition Partnerships and be a driving force for the establishment of an international green taxonomy and green trade rules. The EU also needs to be a global force in pushing for energy and resource sobriety, especially in discussions with large consumers like the US.