The Sino-American rivalry affects the European Union (EU) in the form of a trade and technological conflict. Sino-American decoupling may have negative effects on European economies, caught between American sanctions and Chinese retaliation. The combination of this geoeconomic pressure with more traditional protectionist measures contributes, moreover, to weakening the multilateral trading system.

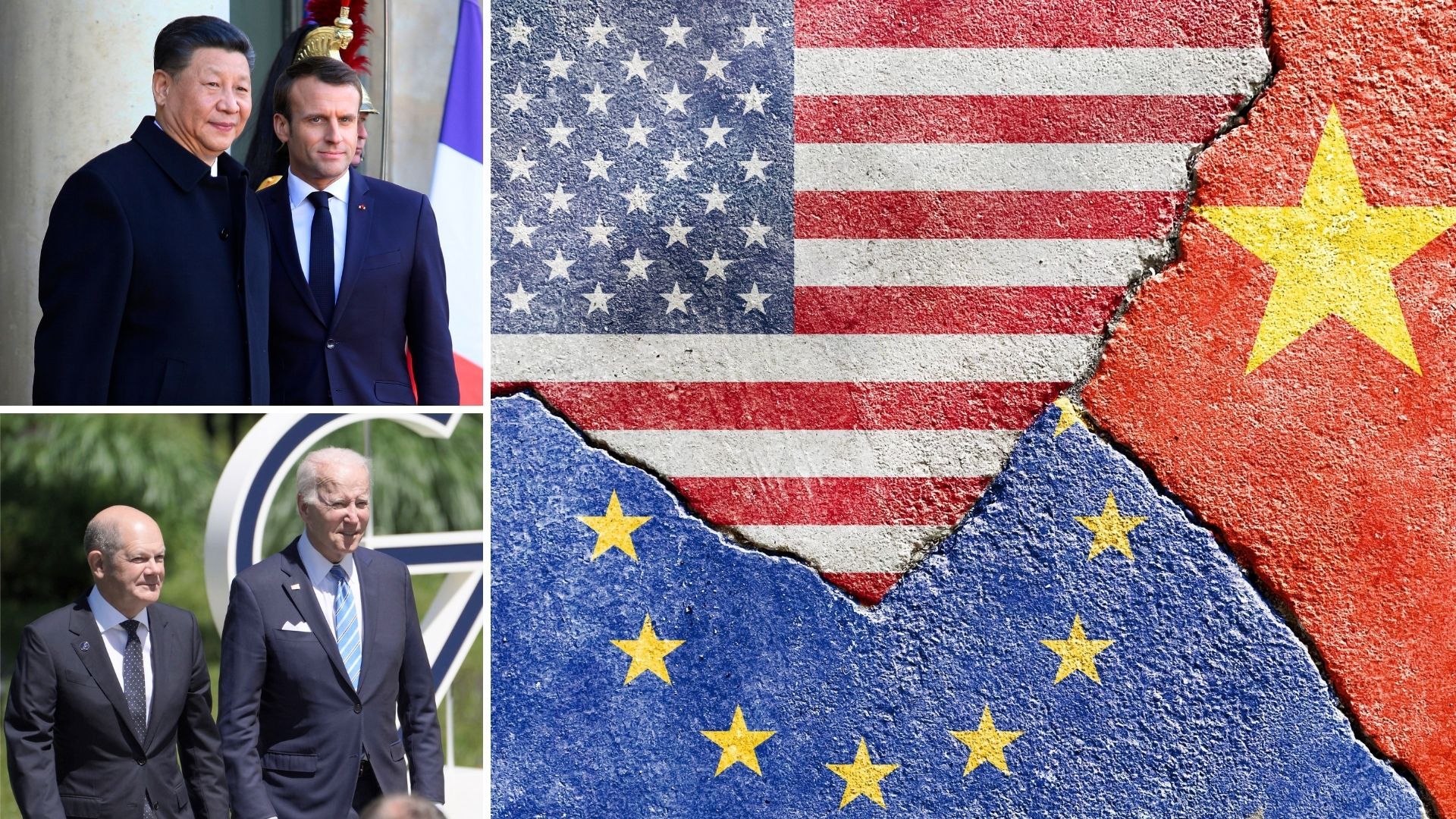

Four years after President Macron staged European unity by receiving Xi Jinping in Paris in the presence of Chancellor Merkel and the president of the European Commission, has the EU managed to define a common approach, allowing it to respond to the challenges of commercial competition and technological security, which have been exacerbated by the Sino-American rivalry?

Over these four years, no significant progress has been made in developing a common, coordinated European approach. What is more, the war in Ukraine has damaged the competitiveness of European economies and brought a new security and diplomatic dimension to relations between the EU, China, and the United States.

The War in Ukraine as Seen from Paris and Berlin

Ever since the war in Ukraine broke out, public debate in Germany has centered around the notion of Zeitenwende (end of an era), a term coined by Chancellor Olaf Scholz in his address to the Bundestag a few days after the Russian invasion. Berlin has faced the need to break free of its dependence on fossil fuels, in particular Russian gas.

In this context, the perception of the challenges linked to the Sino-American rivalry differs on either side of the Rhine. This is primarily due to France and Germany’s differing levels of exposure to risks: for Berlin, which must break free of its dependence on Russian gas, opening a second front with China is not an option, as the Chinese market is an essential outlet for the German economy. In 2019, Germany accounted for 48.5% of EU exports to China. Germany’s market share in China is 5.1%, compared to 1.5% for France.

Franco-German Relations: Between Affirmation of a European Ambition and Bilateral Competition

The coming into power of the coalition led by Chancellor Scholz in autumn 2021 has not yet led to a common Franco-German approach to Beijing and Washington. There are two reasons behind this. First, the war in Ukraine has put the issues of collective security and the provision of military aid to Ukraine at the top of the agenda. This has changed these countries’ relations with the United States, which has asserted its leadership in the coordination of Western aid to Ukraine. Second, the coalition in power in Berlin is working on defining a national security strategy and a China strategy, in order to translate into governmental action the more assertive language contained in the coalition agreement. The laborious negotiations between ministries have delayed the adoption of this strategy. At the same time, the government’s decisions to allow the Chinese company COSCO to buy a 24.9% stake in a terminal of the port of Hamburg and to block the sale of one of Elmos Semiconductor’s chip factories to the Swedish subsidiary of the Chinese company Sai Microelectronics relativizes the importance of such a strategy.

Meanwhile, Paris is taking stock of its dependencies on the Chinese market, which are limited to a few strategic sectors, and favors a strategy of risk reduction based on the reshoring of certain industries. Although the EU is strengthening its toolbox of trade defense instruments around the principle of open strategic autonomy, it has not managed to put forward a model of its own that might allow it to resist the United States’ insistence on decoupling with China, while protecting itself from geoeconomic risks coming from the Chinese side. Beijing’s use of economic coercion against Lithuania on the one hand, and the agreement between the United States, Japan, and the Netherlands to impose restrictions on the export of semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China on the other, are a cruel demonstration of this.

Despite the EU’s aim of projecting an image of unity, the prevailing impression is one of competition between the European capitals, as demonstrated by the German chancellor’s solo visit to Beijing in November 2022, with the French president and the Italian prime minister set to follow suit in April this year.

The war in Ukraine has changed Europe’s position within the Sino-American rivalry. China’s announcement of a “no limits” partnership with Moscow was a wake-up call for Europe regarding the risks posed by Beijing’s position, prompting European countries to strengthen their ties with Washington, which has established itself as the guarantor of their security. As they consider how to organize their economic relations with China while at the same time strengthening the protection of national security, European capitals are exposed to intense pressure from Washington, which will become even stronger if sanctions against China are to be imposed in response to possible arms shipments to Russia. Moreover, the Biden administration’s determination to strengthen the position of the American economy in the competition for green technology, throughout the entire production chain, places the question of the competitiveness of European industry at the center of the debate. This is an essential debate, as reflected in Josep Borrell’s remarks in November 2022 that the EU’s dependence on China for its green transition strategy is greater than its dependence on Russian fossil fuels.